Testing Charma with Selenium

Kyle Niewiada on April 29, 2016

6 Minute Read | Medium project

Updated on June 28, 2021

If you’re wondering what I’m talking about when I mention the word Charma, I’m referring to an open source web API and web application that I built with two other teammates as a sponsored project by Microsoft for my Grand Valley State University senior capstone. You can read about our project along with a video overview here. One of my largest contributions to that project was implementing web browser testing using Selenium.

My Largest Contribution (Selenium)

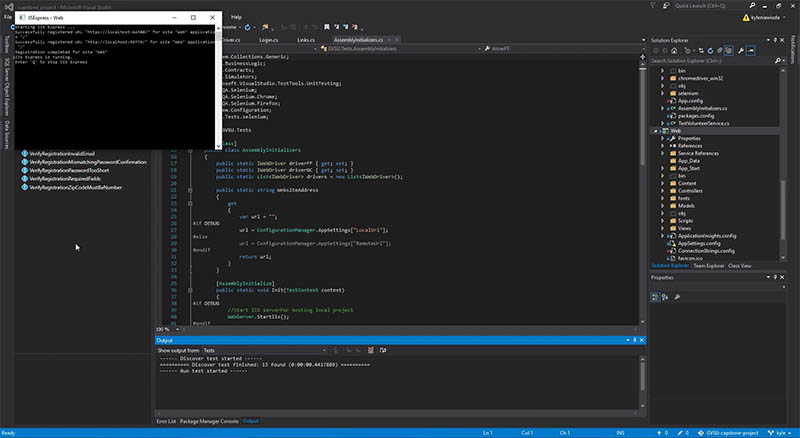

For testing, our group decided to use Selenium WebDriver to test the interactions between our website and other browsers. The Selenium WebDriver allows for automated tasks to be written and run with different web browsers as a user would. It bypasses any cross-origin scripting policies by using a WebDriver to interact with each browser. Such examples for tests include selecting a field, inputting certain information into that field, submitting, and verifying results with what the website responds back with on the screen. Such a test is used on our registration page to verify that bad entries are not submitted and returned with proper error messages.

Before this project, I had never heard of Selenium. I would barely consider myself competent after seeing all the test coverage necessary for a website. Our tests are nowhere near complete. However, it did offer a necessary glimpse and small coverage for web browser automation testing.

In the beginning, when researching the Selenium WebDriver, a decision was made to implement our testing using the browser web drivers. It was not until late in our project that we discovered how slow each implementation of the browser web drivers were. In retrospect, we should have set up was a server to work with the HtmlUnit Driver. Our tests were not necessarily dependent on the ability to drive an actual browser. Using the HtmlUnit Driver would have been significantly faster and independent of the machine we were testing on. The limitations to testing with our webdriver is that we are platform dependent and dependent on the web driver staying up-to-date/compatible with current versions of their respective web browsers. But ahead is the result of my Selenium WebDriver implementation.

To make Selenium WebDriver testing work for our project, we had to make sure that each of us had installed the same web browsers to test with. All of our environments had Google Chrome and Firefox installed. We used the built-in web driver with Selenium for Firefox, and implemented Chromium’s web driver for Google Chrome. Additionally, all testing platforms needed to be on the same operating system because our Google Chrome web driver was OS dependent. Although, now looking back we could have made a check in the code to see which operating system the user was on and then branch to the appropriate web driver.

Setting It Up

To add another web browser or web driver, it is as easy as initializing the web driver for that browser, adding that driver to a global list accessible by the testing suites, starting that web driver, and then stopping it when it is complete.

#if DEBUG

Before our Selenium WebDriver can begin testing our website, we have to initialize the Internet Information Services (IIS) to locally deploy your website after build. Before I figured out how to do this, I manually ran an instance of our web app in the background and then ran the tests. But now the startup of our selenium tests are independent of a manual website launch. Once the Internet Information Service has been initialized, we are ready to begin testing.

#else

When testing in release mode, we will redirect all of our tests to our production webpage hosted on Azure services.

#endif

Running Our Selenium Tests

Each web driver for each web browser is initialized and the testing begins. The very first test we have is browsing to Python.org, searching for pycon, and verifying that results exist. We do this to simply verify whether or not our web drivers are working properly. If we fail, we immediately know that there is something wrong with the initialization or setup of our Selenium WebDrivers.

On the registration page we check for invalid emails, mismatching passwords, passwords that are too short, missing required fields, and ZIP Codes that are not numbers. The entire list of tests for the registration page take roughly 2 seconds for each browser. Next, we verify that all links in the header are what we expect. Such that there are no missing and no extra links in the header of our website. If there is, that would be an example of a routing problem that we may have missed and should inspect immediately. After this, we dynamically grab all links in the header of the website, and test the response code from each URL to verify every link is alive.

Each link is grabbed dynamically such that if we add a new webpage to our website, we do not need to change too many of our tests. We visit each of those links in the header, and upon each page that we visit, we verify that there are no dead images on each page. After a visit to each link has been made, we repeat the same process and check to verify that no dead links exist on any page that we can find. We separate these two cycles to split up our testing methods and to better understand what goes wrong when a test fails. These tests are verified by getting the HTTP response code from each link we find.

After all these tests have run, the web drivers exit, and the Internet Information Services are stopped. The results are then displayed.

Notes

We had to watch out for our Visual Studio Team Foundation Server failing our tests because it did not have the same operating system as the rest of our testing platform. So I set up a category for the Selenium WebDriver tests with the name “Selenium”. This category was then noted and filtered out of the build steps on the Team Foundation Server. This ensured that our tests would not fail online and then fail to deploy our website after pulling the source code from GitHub.

Our web driver tests are set up to allows us to create repeated tests and test these interactions across multiple web browsers dynamically. Our project is set up to maintain a list of all implemented web drivers on the system, and then in parallel will run each test for the list of web browsers.

An unusual note is that we found Firefox to be significantly slower than Google Chrome when it came to interactions with the Selenium WebDriver. I am not entirely sure the reason that this happens.

Final Thoughts

I had a great last semester a Grand Valley State University. I was given the opportunity to work with two other outstanding students and briefly with Eric, our mentor at Microsoft. I learned quite a bit about the enormous scope of our enterprise level MVC ASP.net web application and how much more test coverage we actually needed for our project. Tomorrow I graduate and I begin my software developer career. Here’s to the future.